“The spider is a repairer. If you bash into the web of a spider, she doesn’t get mad. She weaves and repairs it.”

―

History is full of the stories of privileged men. Men of power and terrifying influence who utilize various forms of art (and what is later written of it) to forward their agendas and values. These same men devalued the efforts of women. They took away the value that the everyday, the seemingly “trivial” had and created a society where only the “highest” forms of fine art were legitimate. The art world these days continues, consciously and unconsciously, to play this game and it is up to us to patch the holes, so-to-speak.

Whether in personal situations or in our communities, there are often gaps, areas in need of improvement, support and care. When a fabric is worn so thin that it creates a hole, one may repair the hole by weaving a new fabric over top and through the old fabric using either new threads, similar or completely different ones. This form of patching is typically referred to as darning. Unless something truly drastic happens, this fabric can never be completely remade but it can be patched again and again as needed.

Though MLK Jr. Day has passed, it is vital to continue the conversation about social justice and inequality. That we continue to fight the good fight not just for our friends but for our children and their friends. And that by showing our children how to fight and stand up for what is right, we have a better chance of securing an equal future for them and a continued tradition of equality for all.

However, this idealized outcome does not occur overnight. It does not happen within a week, or a year… it comes from everyone’s devotion and commitment. From the slow and steady ebb and flow of all our efforts never ceasing as we beat against the shores of past injustices. One way I believe this is possible is through community engagement, creating safe public and private spaces for conversation and connection.

In the weeks to come, I will highlight a range of textile artists who use their medium to connect communities and drive forward messages of peace and social justice. Today’s feature is not one but many, many women, a collective located in the Deep South of the United States.

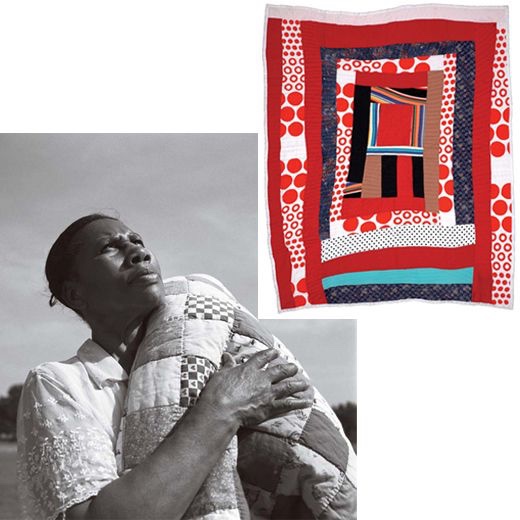

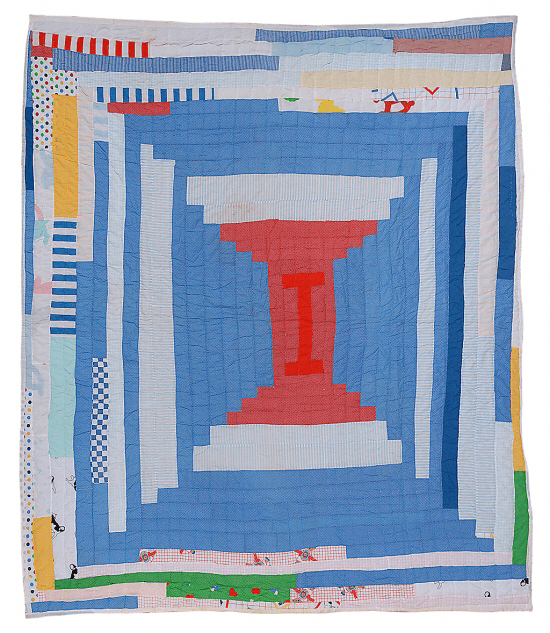

Quilt-making in America is a textile art form with a deeply rich and bittersweet history. Slaves forced to work on plantations would create bed coverings and sacks from clothing that became too ragged to wear. This skill and resourcefulness was passed down to their children and their children’s children. And nowhere in the United States is this tradition stronger than in the small, isolated Alabaman community known as Gee’s Bend.

Gee’s Bend began as a cotton plantation in 1816 with the aid of seventeen slaves and later sold to Mark H. Pettway in 1845. Post-civil war and emancipation, many slaves and their families stayed on as sharecroppers into the 1930s. The region was drastically changed as the Great Depression swept across the nation. When money was low, many Gee’s Bend families borrowed seed and fertilizer at high interest rates from the merchant, E. O. Rentz. Upon his death, Rentz’ widow foreclosed on 60 Gee’s Bend families who were unable to pay the amount due.

“They took everything and left people to die,” Pettway, quilter and descendent of the original land owner said. Her mother was making a quilt out of old clothes when she heard the cries outside. She sewed four wide shirttails into a sack, which the men in the family filled with corn and sweet potatoes and hid in a ditch. When the agent for Rentz’s widow came around to seize the family’s hens, Pettway’s mother threatened him with a hoe. “I’m a good Christian, but I’ll chop his damn brains out,” she said. The man got in his wagon and left. “He didn’t get to my mama that day.”

In 1962, ferry access was cut off from the Gee’s Bend community to the surrounding areas and not restored until 2006, further isolating the already secluded community. However, this did not stop Martin Luther King Jr. from visiting them in 1965.

“I came over here to Gee’s Bend to tell you, You are somebody,” King shouted over a heavy rain late one winter night in 1965. A few days later, Annie Mae Young, one of the prominent quilters, and many of her friends took off their aprons, laid down their hoes and rode over to the county seat of Camden, where they gathered outside the old jailhouse.

Those who chose to march and register to vote lost their jobs and some even their homes. In order to help raise money for the community, Francis X. Walter established the Freedom Quilting Bee in 1966 in order to provide a source of income for the local community. This effort was successful enough to lead to a commission from the Sears, Roebuck and Company to make corduroy cushions. The leftover corduroy scraps were later turned into new quilts, many of which now live in museums.

In 2002, collector William Arnett was so struck by the quality and originality of the Gee’s Bend quilts that he helped organize an exhibition of their work at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, entitled “The Quilts of Gee’s Bend”. This exhibition was somewhat of a saving grace for the Gee’s Bend quilters. Their art had been slowly ebbing out of fashion and the older quilters, in particular, had stopped quilting due to old age and arthritis. As this show gained notoriety and exposure, it renewed their joy of making and several women returned to creating and passing down their traditions. Additionally, the public exposure to this rich history subsequently helped reach a wider, global audience, helping to darn the patches of history.

Curator, Jane Livingston is quoted as saying, that the quilts “rank with the finest abstract art of any tradition.” However, this notation compares them to a world so very different from their own. To simply compare visually to their art world doppelgängers, ignores the community and home from which they came. In a MET interview (referenced below) with author and curator, Amelia Peck, she states…

“To say that they look like abstract paintings is an easy, though superficial, way to understand Gee’s Bend quilts. The women making these quilts never saw the abstract paintings that their work supposedly references. There’s a marketplace component to this view; this comparison was an attempt to raise their value—I’m not talking simply about monetary value, but rather the validity of these quilts as works of art. Earlier generations couldn’t see them as anything other than domestic. “Women” and “domestic” are uncomfortable categories for most classically trained art critics; a useful object made by women for the home that also happened to be beautiful was not considered art. For a long time, critics compared graphic quilts to abstract art painted by men as an easy way to make sense of them and to make them into something more valuable than just a bed covering—more of a “real” work of art.”

These quilts are reflections of their lives, telling both deeply personal as well as mundane stories. They are vibrant reflections of determination, character and defiance in the face of so much adversity. The story of Gee’s Bend and the quilts that are made there is as diverse as the many quilters that came and still live there. The spirit of quilting, of taking pieces of the past to create something anew is, I think, an important lesson from which we can all learn. Quilting continues to be a creative and fruitful outlet for Gee’s Bend women. If you wish to learn more about the individual women and their quilts please follow the sources below, particularly the “Souls Grown Deep” website which is a well-documented site, full of beautiful images and the names/info of many of the quilters.

Thanks for reading!

SOURCES | Further Reading …

Souls Grown Deep “Gee’s Bend Quiltmakers” – http://www.soulsgrowndeep.org/gees-bend-quiltmakers

Smithsonian “Fabric of Their Lives” – https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/fabric-of-their-lives-132757004/

MET Blog “Art on Its Own Terms: Author Amelia Peck on Gee’s Bend Quilts in My Soul Has Grown Deep” – https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2018/amelia-peck-rachel-high-gees-bend-quilts-interview