“Like a circle in a spiral,

like a wheel within a wheel

Never ending or beginning

on an ever spinning reel

As the images unwind,

like the circles that you find

In the windmills of your mind”

The Windmills of the Mind, Alan and Marilyn Bergman

Oftentimes, as we follow an interesting thread of thought, we stumble upon another and another, leading us down a seemingly endless tapestry of ideas. The threads meanders left and right, up and down, and yet still connected somehow (if but distant) to that original thought. Events layer on themselves in a series of spirals, circling in and out, creating a vast web of connections over time. This is true of life as a whole… and this is true for the story of cotton.

When studying cultures and history, there is often the desire to organize and group the narrative into neat boxes. It can be reassuring to us, anxious humans, to have solid truths about this world. However, this is a problematic way to approach historical narrative especially given that reality tends to be much more complex and nuanced. We inhabit a spectrum of greys, not solid black and white boxes. Things, reality, situations, can oftentimes not make sense… and yet time carries on regardless.

Though sugar, tobacco and rice were major global exports in ancient societies, none of them have shaped the world quite like cotton. According to Sven Beckhert’s Empire of Cotton: A Global History, the industry of cotton paved the way for “large industrial proletariats in Europe”, the “rise of vast new manufacturing enterprises”, “huge new markets for European manufacturers” and an “explosion of both slavery and wage labor”. These are the kind of complex, grey, interconnected story threads that I reference above and in the weeks to come I hope to gradually unpack them as we delve further into this unique history.

That said, I’d like you to imagine this early time in our history. The world is still dawning and our ancestors are waking up to the reality of existence. The world’s pre-capitalist, pre-colonialist cultures were thriving as best they could. Colonialism had not yet upended the world. And plastics are a thing of the distant future, another world even.

Across the globe, cultures are taking advantage of their newly non-nomadic lifestyles by devoting their time and energy to advancements in animal husbandry and agriculture. With this backdrop, we see three unique disconnected cultures in Asia, Africa and the Americas, begin cultivating and spinning threads from cotton.

Cotton was cultivated on three different continents throughout the world – the Central Americas, South India and East Africa – all around a similar time frame of 3000-2000 BCE. These three locations were the ideal climate for cotton, which tends to grow best in subtropical climates within 32-37 degrees north and south of the equator. Cotton’s “morphological plasticity” allows it to grow in each region in a variety of ways, reacting to the specific weather patterns, soil content and local predators of its locale.

Most textiles of this time were made from natural materials and, therefore, a great majority of them have been lost to us through time and biological decay. However, archaeologists have found unique fragments in the most severe deserts and tundras of the world which give us clues about ancient societies. In Asia, there is evidence of cotton textile production as far back as 6000 BCE in the pre-Harappan site of Mehrgarh in Baluchistan. Traces of woven cotton were also found at the Mohenjo-daro Indus Valley site as well as spindle whorls from around 2500-2000 BCE. The world’s earliest surviving woven cotton fragment was found near India at the Dhuweila in Jordan, dating from 4450-3000 BCE and believed to be imported from the Indus Valley area. Seen here is a stone impression of an ancient cotton weave discovered in the Harappa site, home to the Indus Valley Civilization.

In Central America, one of the oldest cotton textile fragments was found at the Huaca Prieta archaeological site in Peru, dating from around 3800-4000 BCE. Though small, this fragment shows an early mastery of woven patterns and dyeing traditions. This fragment is also one of the oldest known indigo-dyed fragments in the world. In Pre-Columbian Mexico, researchers have determined that they produced an outstanding 116 million lbs of cotton each year, equal to the United States’ cotton crop of 1816.

In Africa, it is believed that cotton was first cultivated by the Nubians (near Eastern Sudan today) around 5000 BCE. However, archeological evidence from the Meroe Archeological site only supports around 500-300 BCE. Below is a stunning textile, currently housed in the British Museum, from this site. If you are curious to learn more about it and the other textiles from this dig, Dr. Elsa Yvanez has a wonderful site devoted to the topic.

According to Beckhert, cotton was not a significant crop to Egyptians until around 332-395 BCE. Eventually, cotton came to thrive in West Africa but the route of that journey is still unclear. Islam began to spread throughout Africa in the 8th century CE and cotton, due to its natural white color, spread with it. By the 11th century, there is evidence of cotton spinning and weaving in West Africa and, by the 16th century, the Western kingdoms of Mali and Timbuktu had a great abundance of and thrived due to cotton.

During this pre-modern/ancient era (in this case, I mean roughly 3000 BCE to about 1600 CE), cotton production was so important to pre-modern society that the major ruling bodies of each country demanded it annually like taxes from the inhabitants of that region. As with most crops during this time, families would grow their cotton plants alongside their other food crops. It was as valuable as money, if not more so, due to its usefulness and the fact that the majority of the world was still using the bartering system at this time. One could buy most anything with cotton at this point in history.

As global populations rose, so did the demand for cotton. All around the world, from 4th century Ming China to Islamic cities like Mosul, large cotton workshops became more common. This, in turn, created a new type of weaver – an individual, usually male, who created for a market. The cotton workshops created a diverse network of global commerce connected by merchant capital. The control of the weaver versus that of the merchant varied from region to region. In India, weavers relied on merchants for capital but had control over their own tools and disposal of products. However, in China, cotton merchants would buy up raw cotton, have it spun and woven by peasant women, dyed in workshops and then exported throughout China for sale. Innovations in cotton tools, such as ceramic spindle whorls in Mesoamerica and the roller gin in Asia, as well as domestication of cotton plants for textile production, helped cotton textile production in these pre-modern societies flourish.

By the 1600s, Indians had so mastered the craft of textile production that the famous explorer Marco Polo is noted as saying their wovens were like “webs of woven wind”. In the 17th century, an Ottoman official once said, “So much cash treasury goes for Indian merchandise that… the world’s wealth accumulates in India.” And it was true! Indian cottons are considered by historian Beverly Lemire to be the first “global consumer commodity” for not only the way in which desire for them spread worldwide but also how common Indian fabric terms became household name – such as chintz and jackonet (from the Indian “chīnt” meaning “spotless” and “Jagannāth”, an Indian seaport).

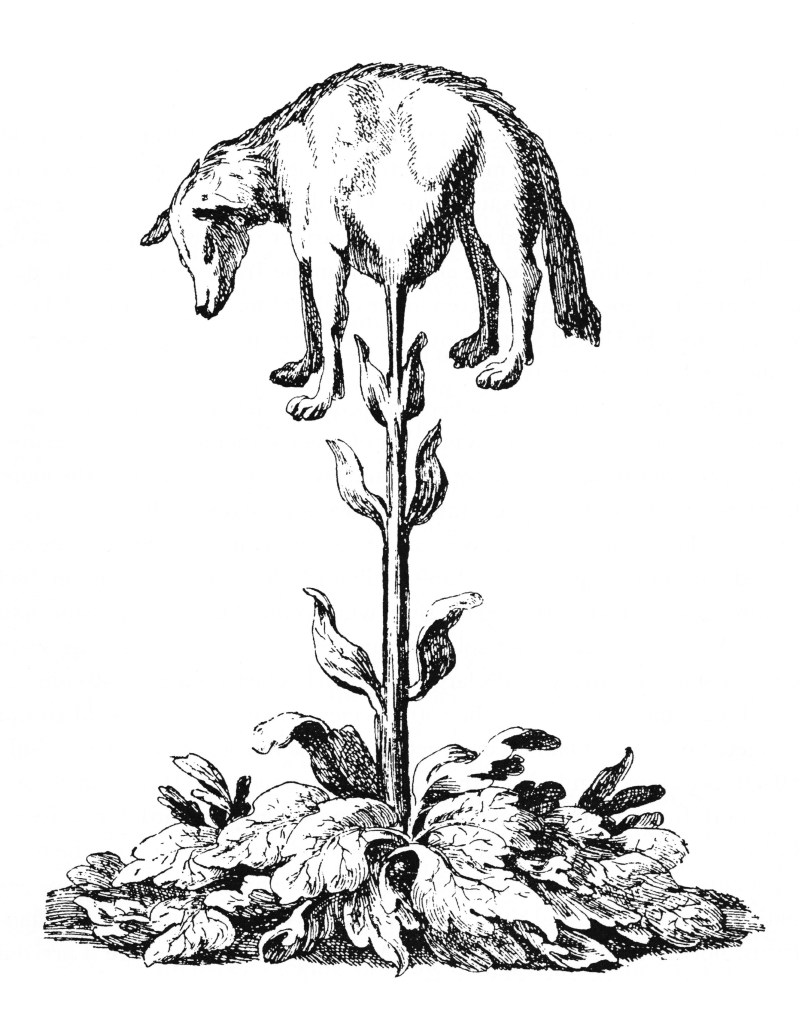

Meanwhile in Europe, people were largely unfamiliar with this seemingly exotic cotton plant, depending more heavily on linen and wool. Part-plant, part-animal, some Europeans imagined cotton as a sort of “vegetable lamb”, one Medieval illustration picturing it as such…

In around 950 CE, there existed a moderate cotton industry in the southern regions of Italy, largely due to Islamic influence. The Arabic word for cotton, qutun, is where the English, French, Spanish, Portugese, Dutch and Italian terms for cotton are derived. It wasn’t until the 12th century that Europe saw a “massive infusion of outside technology” such as the spinning wheel and horizontal treadle loom.

While Europe still largely depended on wool and linen during this time, Italy and Germany developed their own cotton textile productions. Northern Italy was successful early on due to a legacy of skilled textile workers, easy access to raw material and access to “Eastern” technologies to aid their industry. The Germans were more organized in their approach. Similarly, they had access to skilled textile workers and raw cotton but they also took greater advantage of cheap labor and tapped into trading throughout European markets, even parts of Italy! However, everything changed when the Ottoman Empire consolidated hold on the realm in the 1560s, collapsing the flow of raw cotton to German and Italian textile-producing cities.

This lack of access to the original source of cotton would be remembered in the century ahead when European countries begin to make forceful strides into the global market through a tactic, Beckert terms, “War Capitalism”. More on this in my next post.

SELF-EDU UPDATE

Since my last post, I’ve already started realizing some things I want to tweak with the flow of my studies. In a college setting, you have the aid of a teacher who has the curriculum lined out, is a specialist in their field and, in some cases, has taught the classes several times. I am no specialist and I am learning as I go. The reality of taking three self-taught classes in four months (that includes researching, ordering and preparing the materials in the first month) while continuing to work was overly ambitious for me. However, I am really enjoying diving into the subjects so I’ve decided to extend the curriculum I am currently working on through the end of the year. To effectively do this, I’ve realized it will be more worthwhile to focus on one subject and one form of making at a time. So rather than speed through two fairly dense topics (the history of cotton and the history of hand knitting), I’ll be focusing on one (the history of cotton) and supplementing that with learning how to use Procreate on my iPad. And that, my friends, is the beautiful thing about self-education – you are your own boss! You can easily control the speed of the content and, with some form of public accountability, continue to make progress without overstressing or throwing in the towel altogether.

The story of cotton is so vast and I couldn’t possibly do it justice in the course of three months or even three years of blog posts. Since the title of this “course” is technically “Cottons & Quilts: A Dive into Early African American Textiles”, I hope to hone in further and further on that subject as I progress in my reading. I am curious about the migration of African culture into the Americas as well as how it intersects with European and Indigenous cultures of the Americas. The book I am currently reading gives a broad overview of the impacts of the cotton industry on a global scale. So, it is my intention with these first few posts, to set the contextual stage wherein this topic originates. I think following a narrative from its earliest source is an important part of learning and comprehension. Many facts are omitted along the way for the sake of clarity and time but I encourage you to follow your own curiosity and seek out the references listed at the end of each post.

Thanks for reading!

References

Beckert, Sven. Empire of Cotton: A Global History. Vintage Books, 2015.

Crill, Rosemary. The Fabric of India. V&A Publishing, 2015.

Khan, Omar, et al. “Empire of Cotton.” Harappa.com, 7 Dec. 2015, www.harappa.com/blog/empire-cotton.

Yvanez, Elsa. “The Basics of Meroitic Textiles.” TexMeroe Project, 29 Apr. 2018, http://texmeroe.com/2018/04/29/the-basics-of-meroitic-textiles/

Further Reading

History and Glossary of African Fabrics- https://youramba.com/blogs/news/50891267-history-and-glossary-of-african-fabrics

Google Arts & Culture Slideshow: The Fabric of Africa

Cotton in Ancient Sudan & Nubia

https://journals.openedition.org/ethnoecologie/4429?lang=en

Re-excavating SJE 350/II – Nubian Burial Site