We arrive on this earth innocent, having no memories except perhaps those of our ancestors carried in our genes. We hope those around us will guide and teach us what we need to know. Social constructs constructed before our arrival pre-determining so many things about us and how our lives will enfold. Chance and circumstance naturally mixed in based on the whim of a greater power.

As humans born in the 20th and 21st centuries, I think there is a tendency for us to normalize our current world. To take for granted the people before us, the layers of history and the many trials and triumphs that have brought us to this point. We often take for granted our access to technology when, in reality, the world as we know it now has only very recently come into being, the result of a complex global system.

The majority of this post will focus on the early economic history of the modern cotton industry and not as much on the textiles themselves. The study of cotton would not be complete without this understanding and that fact is becoming increasingly clear as I slowly progress through Sven Beckhert’s Empire of Cotton, my main reference on this specific topic. He is the one who coined the term “war capitalism”, which, to some, may sound extreme at first but it accurately paints the picture of the extreme measures taken in the era it flourished. To quote Beckhert, “a term like ‘war capitalism’ is intended to convey the violent appropriation of the economic market through the unrestricted actions of private individuals and the protection of such actions by states.” The story of the by-product of this industry – the quilts of slaves, their descendants, and black quilt artists across America – would be incomplete without factoring in the violent past that led to their very existence.

Building War Capitalism (1600s – 1770s)

After the expeditions of Christopher Columbus and Vasco da Gama in the 1490s, the world started to grow smaller and more connected each proceeding century. The colonizing countries more and more aggressively sought out how to take advantage of the “New” World – Spain connecting to the Aztec Empire, Portugal to Brazil, and France and Britain to Canada, the American colonies, and the Caribbean.

By the 1600s, Europeans were still largely dressing in wools and linens but, in the following centuries, merchants would gradually and violently take control of the global networks of the cotton trade. After usurping the Portugese East India Company’s power in India in the early 17th century, the British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company fought each other as well eventually dividing up Asia with the majority of trade in India going to Britain.

Cotton cloth was the British East India Company’s most valuable good and it was used threefold: for trading spices in Southeast Asia, for shipping to Africa to pay for slaves to work American plantations and for domestic consumption in Britain. This is noted as the first time cotton has been entangled in a three-continent-spanning trade system. Beckhert writes, “Never before had the products of Indian weavers paid for slaves in Africa to work on the plantations in the Americas to produce agricultural commodities for European consumers…These three moves – imperial expansion, expropriation, and slavery – became central to the forging of a new global economic order and eventually the emergence of capitalism” (Beckhert, 36-37).

At this time, European merchants were dependent on local relationship managers called banias who were the gateway between them and the local farmers and weavers. Factory warehouses were set up by the coast to grade and prep fabric coming in from the Indian countryside.

While busy building up connections in India, Europeans also established themselves in the East African markets. In the 1670s, British merchants witnessed Middle Eastern merchants carrying “off five times as many calicoes” from India then themselves and the Dutch. Enraged by this and powered by their need for control and wealth, they sought to change this by relying on their more formidable boats and firepower, eventually commandeering the majority of trade on both sides of the Indian Ocean.

This tactic of war capitalism relied on an inside/outside dichotomy. The rules of their country (inside) did not apply to what the merchants, military and businessmen did beyond (outside). The inside was governed by rules, law, order and outside was all about domination, being above the law, theft and enslavement. It was not by technical invention or dexterous skill that Europeans were able to climb to the top of the world’s socio economic system but rather through their devious tactics, military strength, control, violence and coercion.

As early as 1621, London wool merchants protested against cotton cloth imports as they were hurting domestic business. By 1678, there was a growing tension around imported goods with people saying, we “wear many forgeign commodities instead of our own.” This is interesting to note because that is a given in the world we live in today and not seen as a negative thing. However, there is great power in sourcing, producing and buying locally made (or making yourself) clothing. Something we are already seeing a resurgence in throughout the world as a resistance to fast fashion. In the 1770s, laws were put in place criminalizing the selling of Indian cottons but this only spurred merchants and states to further dominate global networks of cotton.

By the 1790s, the British East India Company was encouraging Indian weavers to move to Bombay where they could further control them and not be extorted by the “servants of the Rajak of Travancore” and a new system of taxation penalized weavers who produced for others. With these developments, violence escalated and, as the city of Bombay grew, one’s standard of living declined and weaver mortality rates rose. Unsurprisingly, European merchants gained enormous wealth from trade and could demand political protections from their governments which were increasingly dependent on extracting revenue from the trade business. This style of industrial growth through the use of War Capitalist tactics also nourished the development of secondary sectors like insurance, finance, shipping, government credit, banks, and national defense.

The Wages of War Capitalism (1770s – 1850s)

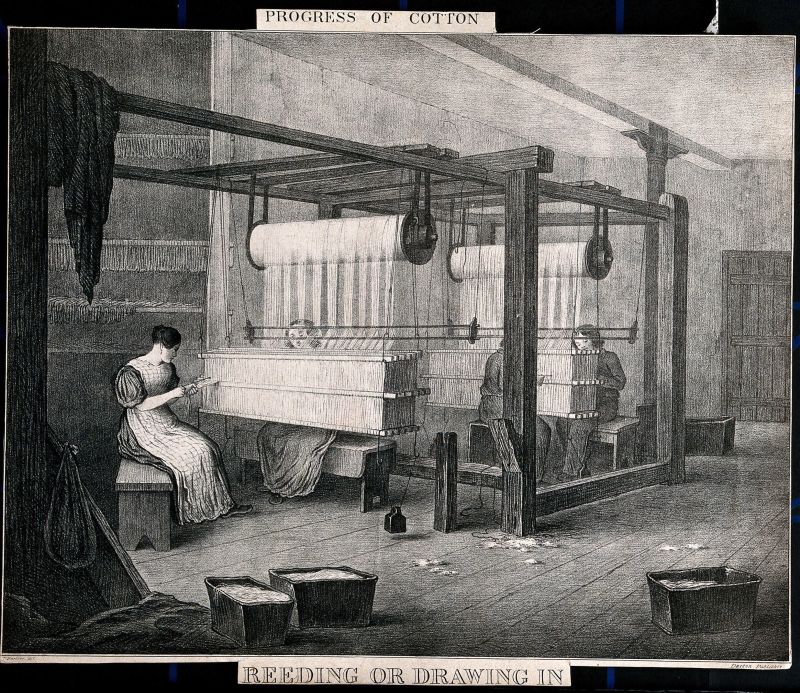

Prior to the 1770s, the cotton industry largely depended on India to produce and weave the cotton cloth. After the 1770s, as you will see, there is a great shift in this dependence and Europe further subjugates the entire industry. In the late 18th century, idyllic and unsuspecting British towns like Manchester and Lancashire would become the global center for cotton production and innovation.

In 1769, Richard Arkwright patented the technology for a spinning water frame, a device that would manufacture yarn using hydropower. This is considered the first time in human history that machines powered by non-animate energy manufacture yarn. Beckert is careful to point out that in early 14th century China, there is an account of a machine for spinning hemp thread that appears to be water-powered. Additionally, water frames in general have existed since ancient Egyptian times. However, the difference between these instances is the global power shift happening in the world. Thanks to war capitalism, England had both ample capital and power to effectively create, patent and use these machines on a massive scale. Additionally, there are numerous cultural/gender/political differences that may have made some countries less likely to mobilize and embrace new systems.

An early manufacturing pioneer was Samuel Greg who, in 1784, set up a small-scale version of what we now call a factory. This factory started off with a few water frame spinning machines, around 90 “Parrish apprentices” (i.e. orphans), some wage workers and a supply of Caribbean cotton. Samuel Greg was an especially privileged man for his time and had a variety of benefits that aided him in setting up this factory. He owned a profitable Caribbean plantation, hundreds of slaves, and was married to a woman whose family business was in the slave trade. He was raised by his wealthy Uncles who gave him the initial capital to set up this cotton manufacturing business and his sister-in-law was in the business of exporting cotton cloth to Africa, a common practice at the time as previously mentioned. It was common practice for cotton manufacturers in Europe to draw their essential raw material from slave labor in colonies, such as the Caribbean.

Back in the hills of Manchester, with the introduction and mobilization of the factory system comes another key modern figure – the manufacturer. They were responsible for on-the-ground organization of workers and machine-based production, which, in turn, gave us a new approach to organizing land, labor and resources. Beckhert emphasizes that this era, the one in which the factory is first formed in this country/context, is marked by “a new institutional form for organizing economic activity and a world economy in which rapid growth and ceaseless reinvention of production become the norm, not the exception” (63). When I first read this, I couldn’t help but think of our current situation. The idea of never being satisfied with what we have, to be constantly buying new things, or upgrading to the latest tech gadget. Contentment has always been difficult for humans to come to terms with and now, more than ever, it feels like we are coming to a tipping point with this sentiment.

All that to say, the ideals of consumerism are not new evident from this account of early industrial history, but they are more obviously in our face due to technology. So, with this mindset, the inventors of the mid to late 1700s went to work. The main obstacle at the time was competing with inexpensive, high quality Indian cottons. Wages in the United Kingdom were much higher than the global average and, because of that, British merchants, inventors, manufacturers focused on how to get the most work out of this high cost labor. Here’s an overview of some of the inventions that made that possible:

In 1733, John Kay created the flying shuttle, which was not widely adopted until 1745.

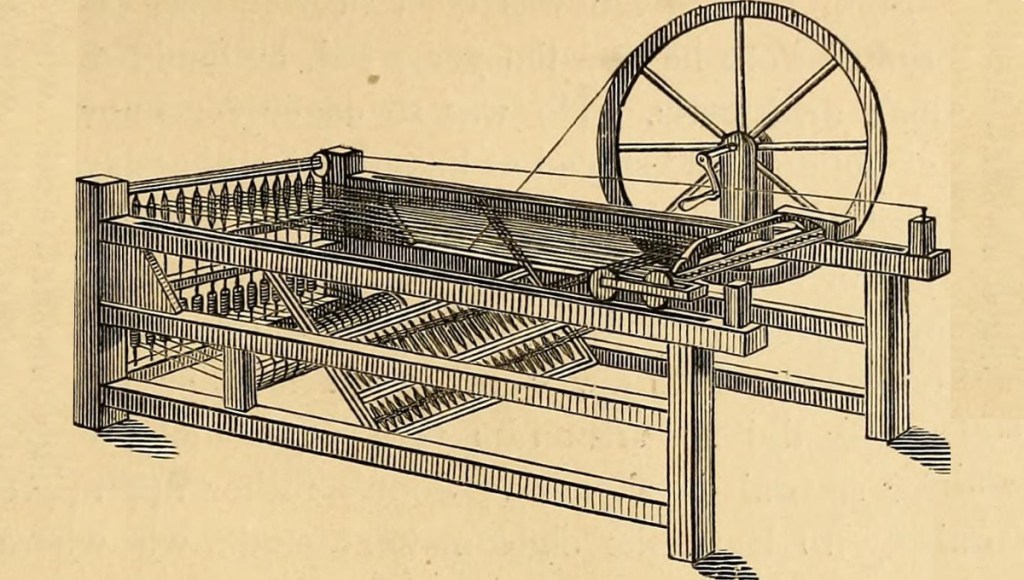

In the 1760s, the spinning jenny was invented by James Hargreaves and, by 1786, there were about 20,000 in use throughout Britain.

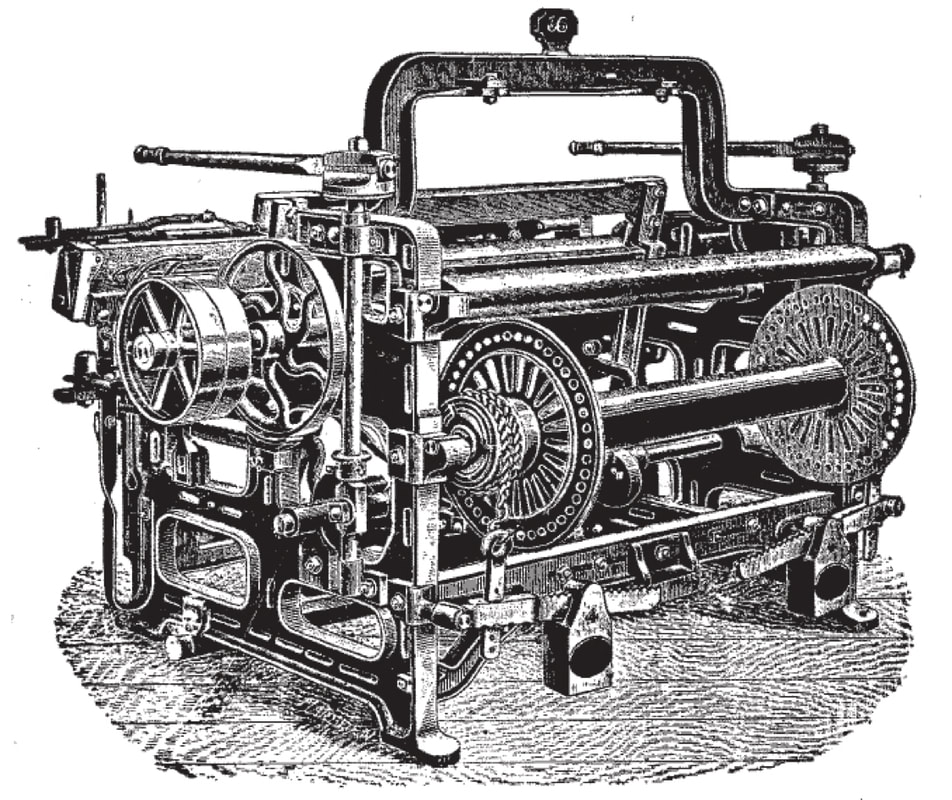

In 1779, Samuel Crompton created the spinning mule.

In 1785, Edmund Cartwright invented the water power loom.

While these inventions all made a significant impact on the textile industry, most of these inventors did not profit from their inventions and either died in poverty or were attacked/isolated by neighbors who opposed their inventions. However, in the end, their inventions worked and, in the 18th century, the UK was able to produce 100 lbs of cotton in 1,000 hours compared to India’s 50,000 hours for the same amount of cotton. By 1795, the number of hours decreased to 300 and, by 1825, that number was only 135 for the same amount of cotton. By 1830, British cotton yarn was cheaper than Indian cotton yarn of the same quality.

Between 1780-1800, output grew 10.8% annually and export grew 14% annually. With cotton’s increasing profitability, the value of cotton to the country’s economy as a whole rose as well. By the 1830s, one in six Britains labored in the cotton industry. A large part of this boom was an export boom since their high quality cottons were now cheaper than India and they were able to take a portion of that consumer base. This, in turn, created a lot of poverty in India, with the value of cotton from Dhaka falling by 50% in the last half of the 18th century. With all this demand, we see the demand for raw cotton skyrocket. This means more land is needed for cotton cultivation and more slaves are needed to pick the cotton.

Capturing Labor, Conquering Land

“The beating heart of this new system was slavery. The deportation of many millions of africans to the Americas intensified connections to India because it increased pressure to secure more cotton cloth.”

Beckhert, 37.

As the cotton industry expanded exponentially on a global scale, so too did the need for an equally large slave labor industry. In the first 5,000 years of cotton’s history, slavery did not play a huge role in the story of its production. However, that was soon about to change.

For the British cotton manufacturing industry to be sustainable, everything had to be in alignment and global connections needed to be made. Asian technology, African markets, African labor and raw cotton from another continent (i.e. the colonies) were essential to its success. And another key ingredient was the use of coercion, which “opened fresh lands and mobilized new labor”, a euphemism for subjugating native populations of their ancestral lands and forcing Africans into inescapable and difficult unpaid work.

Britain first tried to acquire cotton a little closer to home from both the Ottoman Empire and India, however, both proved inadequate over time due to local resistance as well as Britain’s increasing appetite for an endless supply of cotton.

The first two main sources of raw cotton were found in the West Indies and South America where land and labor were plenty. Due to European sugar consumption, the Caribbean had already experienced nearly two centuries of growing resources for European consumption. In the 1780s, cotton imports from the British-controlled islands quadrupled and France followed suit with their colony, Saint Dominique, which Britain was able to profit from. The islands of Jamaica, Grenada, Dominica and Barbados all started growing and shipping cotton to the United Kingdom. Between 1768-1789, Barbados’ cotton exports increased from 240,000 lbs to 2.6 million lbs. Needless to say, the need for free labor was high and many slaves were shipped to the West Indies. Between 1784-1792, an estimated quarter of a million were brought to Saint Dominique alone.

In the words of Beckhert,

“Slavery was as essential to the new empire of cotton as proper climate and good soil. It was slavery that allowed these planters to respond rapidly to rising prices and expanding markets. Slavery allowed not only for the mobilization of very large numbers of workers on very short notice, but also for a regime of violent supervision and virtually ceaseless exploitation that matched the needs of a crop that was, in the cold language of economists, ‘effort intensive’. Tellingly, many of the slaves who were doing the backbreaking labor to grow cotton had been and were still being sold for cotton cloth that the European East India companies shipped from various parts of India to western Africa.”

Beckhert, 91.

A staggering 46% of all slaves sold to the Americas between 1492 and 1888 arrived there in the years after 1780. In South America, Guyana saw 862% rise in their cotton production between 1789-1802 fueled by the import of 20,000 slaves. Brazil supplemented Caribbean exports and soon surpassed it. In 1792, nearly 8 million lbs of long staple cotton, good for factory production, landed in Great Britain each year.

After a decline in cotton exports in 1790, Saint Dominique saw the largest slave revolt in history that eventually led to the creation of the island nation known today as Haiti in 1804. I created a short post about this event and one of its main heroes here. In 1793, due to war, Britain severed business relations with France which forced them to turn to a new source for cotton – the American South.

Slavery Takes Command

As late as 1785, cotton sent from North America to the United Kingdom was rare and one ship’s imports were impounded because it was so unbelievable that it could be from the United States. Britain had an impression that the United States plantations were used primarily for tobacco, rice, sugar and indigo but not cotton. However, as early as 1607, settlers in Jamestown had been growing cotton to cloth themselves and, in the late 17th century, cotton seeds from Cyprus and Izmir made their way to American soil. Americans were known to grow cotton during the struggle for Independence as well as when markets for American tobacco and rice were low.

After France cut ties with Haiti, French and British cotton planters and manufacturers were eager to move their lethal business model elsewhere. The relationship forcibly forged between slavery and cotton in the West Indies was essentially shifted to the seemingly “empty” lands of the United States. Slaves were even marketed for their knowledge of growing cotton.

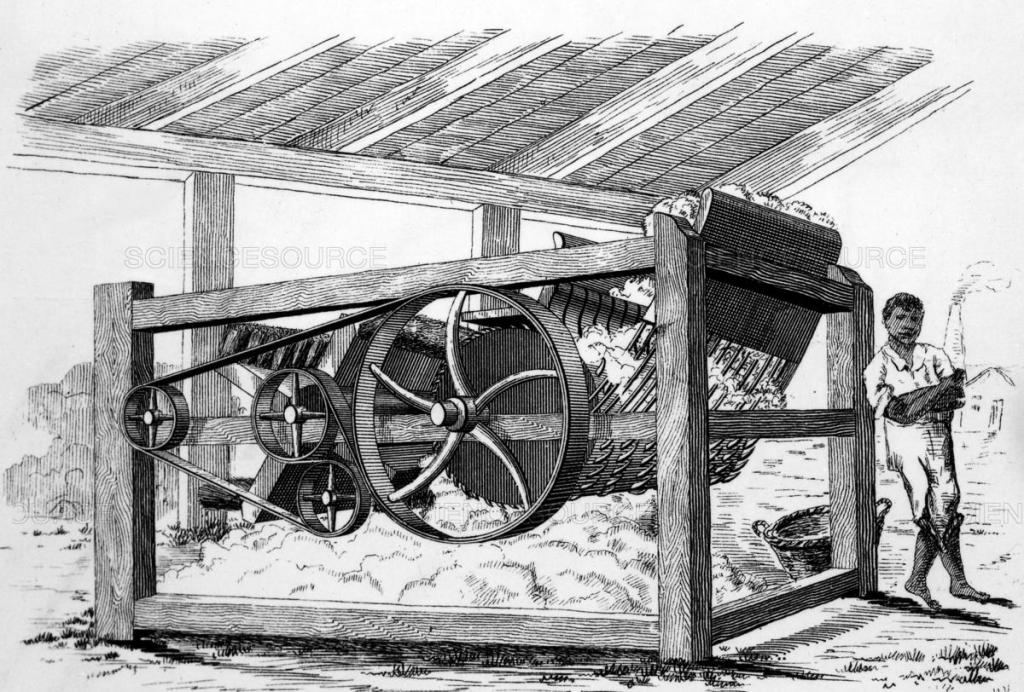

In Georgia, Frank Levett was among the first to start growing Sea Island cotton. And nearby in South Carolina, cotton exports grew from 10,000 lbs to 6.4 million lbs between 1790 – 1800. Eventually, Sea Island cotton gave way to the hardier Upland cotton variety for its hardiness and ability to more easily grow inland. In 1793, Eli Whitney patented the cotton gin, modeled after the Indian churka or charka, as seen in the photograph below. And this allowed for the “cotton rush” to boom even more, nearly doubling profits.

Berar, India, 1866, Photographer unknown.

From the late 18th century all the way to the Civil War era, the production of cotton and the use of slave labor would expand together in lockstep. Early on in America’s cotton boom, Georgia’s slave population nearly doubled to 60,000. Britain had such an appetite for large amounts of cotton and continued to feed this system. In 1790, U.S. cotton production saw such a sharp spike that it is estimated 1.5 million lbs of cotton were produced that year, 36.5 million lbs in 1800 and an outstanding 167.5 million lbs in 1820. By 1857, the United States, still a young nation, produced as much cotton as China and this was all possible because of a system unique to this country- plantation slavery. The U.S. was distinctly successful in forcing slave labor on a massive scale due to their “nearly unlimited supply of land, labor and capital as well as unparalleled political power” (105). War capitalism was the foundation that laid the groundwork for the success of these ventures.

Cotton is not a totally sustainable crop however. After a few years, cotton exhausts the soil and one must either plant new crops (i.e. legumes) or treat it with guano (i.e. bird and bat excrement, which would have been expensive). As a result, planters moved further West and South, continuing to further encroach on the land of native populations. In 1850, it is estimated that 67% of U.S. cotton grew on land that had not been part of the U.S. a century earlier. In 1836, federal troops began forcibly removing Cherokee tribe members from their ancestral homeland in Georgia so it could be turned into a cotton plantation. Upon removal, Cherokee Chief, John Ross, wrote this in response to Congress, “Our property may be plundered before our eyes; violence may be committed on our persons; even our lives may be taken away, and there is none to regard our complaints. We are denationalized; we are disenfranchised. We are deprived of membership in the human family!”

So, not only do we have mass amounts of enslaved (mostly) African people working in the U.S. but we also see a huge decline in native populations, and with them their culture, heritage and way of life. His words ring powerfully even still and I can’t help but think of the recent events surrounding the Dakota Access Pipeline Protests and similar protests regarding sacred land and access to natural resources.

By 1830, 1 million people (1 in 13 Americans) grew cotton, mostly slaves. Between 1783-1808, 170,000 slaves were imported into the U.S. (⅓ of all slaves imported to North America since 1619). Many slaves have since testified in vivid detail the violence of slavery. In 1854, a fugitive slave, John Brown, remembers how he was “flogged… with the cow-hide” and “when the price [of cotton] rises in the English market … the poor slaves immediately feel the effects, for they are harder driven, and the whip is kept more constantly going” (110).

Dependent on slavery to keep their cotton production moving, growing and profitable, America was unable to abolish slavery till 1865. Britain, on the other hand, was able to abolish it in 1834 and yet still profit off of it from across the pond. I think oftentimes this is seen as a progressive move for Great Britain since they did it earlier than the U.S. but they were still hugely profiting from it. Institutional links between the Southern United States and Europe deepened. Mortgages were taken out on slaves, 88% of loans in Louisiana used slaves as partial collateral.

“Slave traders, pens, auction houses and the attendant physical and psychological violence of holding millions in bondage were of central importance to the expansion of cotton production in the United States and the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain” (110). I would argue that this collection of physical and psychological trauma has likely been passed down through the generations and manifests in the way we treat people of color in the U.S. today.

In 1806, Walter Burling, a Natchez planter, brought a new cotton variety from Mexico that was developed by the Ameriindians. Sadly, due to this variety, it gave the impetus to further expropriate more land from the very people who developed it and made slave labor even more productive. As we have seen, coerced labor meant rapid profits, annual returns of 22.5%. As Beckhert writes, “Slavery had enabled industrial takeoff and now became integral to its continued expansion…. It was on the back of cotton and thus on the backs of slaves, that the U.S. economy ascended in the world.” (117-119).

By 1850, 3.5 million British citizens were employed in the cotton industry. As the United States grew into its own nation, them and their cotton production increasingly posed a threat to the continued growth of wealth in the United Kingdom. According to Beckhert, American cotton production became gradually more unstable for three reasons:

- Gradual siphoning off of resources domestically

- Competition globally

- Slave labor system

Given that, Britain’s focus steadily shifts to India for a non-American source of raw cotton. There were many initiatives to increase Indian cotton exports to Britain such as introducing the U.S.-born cotton planters to create wage labor cotton farms, but they were unsuccessful for a variety of reasons (pp 127). The “militarized agriculture” of the United States was against India’s way of life. Monocultural production of cotton lost out to subsistence crops that planters cultivated in order to ensure their own survival. Additionally, Indian cultivators demanded steeper prices when selling anything to European merchants, due in part to their violent past. Thankfully, the system of plantation cotton production that flourished in the U.S. was not able to occur in India, West Africa or Anatolia (all places where Great Britain attempted a connection) due to resistance to bodily coercion and land expropriation.

Final Thoughts

So, why is any of this important?

Three main reasons come to mind:

- Foundation of unsustainable system of spending

- Emotional trauma of slavery passed down the generations

- Lack of representation in Museums and beyond

Firstly, cotton and, later slavery, completely transformed the way the world interconnects as well as the development of American social and economic history. Europe’s “ceaseless innovation” mindset clearly dominated this era but none of the frivolities or inventions from this time would have been possible without the proper conditions of privilege and wealth, largely made from war capitalist tactics. That system laid the groundwork for the current-day capitalism that relies on endless spending and increasingly cheap quality and labor. On this point, however, I am hopeful as more people are globally waking up to the reality of what a mechanized future might look like. It’s not a fulfilling one. Humans are meant to work with their hands, it connects us with our ancestors, with nature, and is a fundamental part of who we are as a species. Many people, who are fortunate enough, have already returned to the land and are carving out meaningful lives with our own hands (I enjoyed Melanie Falick’s book on the topic, Making a Life, though the lack of diversity left something to be desired).

Secondly, slavery was a tragic, traumatic event that continues to haunt the United States. The cotton boom was real and clearly would not have exploded in the way it had without the use of unpaid coerced labor. It fed the cotton capitalist complex which in turn fed many other institutions we have today as mentioned above. And this trauma is real and still exists. To supplement this post, I recommend reading through the New York Times’ 1619 Project and listening to their podcast of the same name. Additionally, the On Being podcast had a great episode touching on the topic of epigenetics and the ancestral traumas that are carried through generations.

Lastly, I’d like you to consider for a moment the many beautiful textiles and dresses that are housed in museums from the 18th and 19th centuries. The hands of slaves are as much a part of their production as anyone but where is their recognition? I can’t recall ever seeing a museum object label attributing its creation to an “unknown slave” but this information should be as important as the year. While museum labels tend to be concise, this doesn’t accurately educate the public on the full history of the object. Now, of course, the problem with museums is a deep-rooted issue stemming from Europe’s colonialist past and museums, as we know them today, might not exist without this history. However, if the purpose of a museum now is to inspire and educate the public then the full story must be told as often as possible.

What’s Next?

Phew…

Thank you for making it to the end of this post! Though this history is disheartening, I think it is a very important part of our country and speaks to why our nation continues to struggle for equality and slowing down the consumerist treadmill.

I wanted to end with a quick update about my self titled, “DIY Master” program and a look ahead to what’s next. Beyond cotton studies, I was also learning to use Procreate but I haven’t made much progress with that and, I think, for good reason. At my job, I spend the majority of the day on screens, so when it comes time for me to make things, I find myself eager for that tactile, screen-less experience. That is something that making art on an iPad does not provide. And so, for now, I’ve decided to put my Procreate classes on the back-burner until I can better appreciate working in that medium.

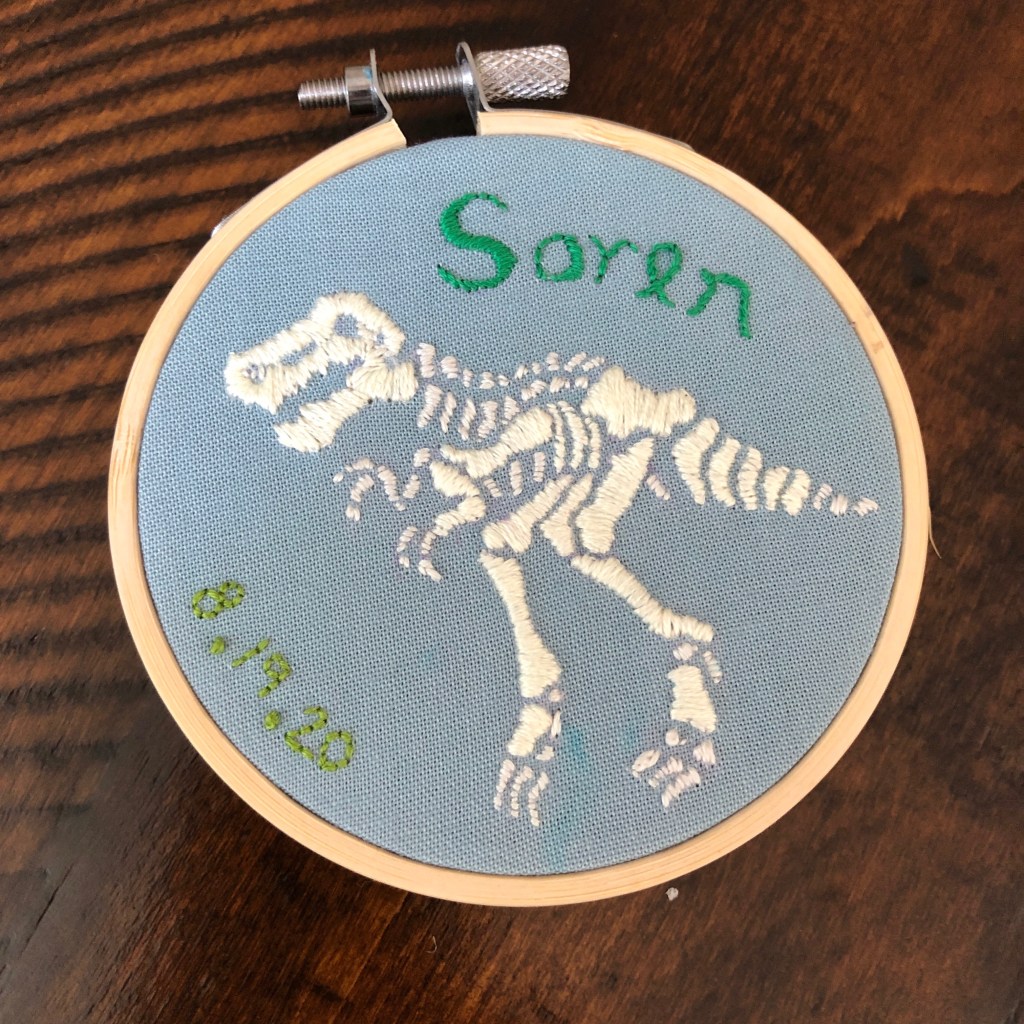

In the meantime, I’ve been making little tactile projects like these…

For the future, I look forward to my upcoming posts being shorter, less heavy and more textile-focused! I’ll be reading through Signs & Symbols: African Images in African American Quilts by Maude Wahlman, Gee’s Bend: The Architecture of the Quilt by William Arnett, (the controversial) Hidden in Plain View: Quilts of the Underground Railroad by Jaqueline Tobin and Raymond G. Dobard as well as supplementary articles and titles, which I will provide links for later.

While I have enjoyed learning about the history of cotton, I am looking forward to getting back into my research on wool Felt. Once I feel like I have achieved my learning objectives in the area of American cotton & quilt history, I will pivot to that. 😊

Until next time, thanks for reading!

References

Beckert, Sven. Empire of Cotton: A Global History. Vintage Books, a Division of Penguin Random House LLC, 2015.

All image sources (except personal ones) are linked to reference articles when you click on them.

Very thought provoking post!

LikeLike